I Went Down to The Crossroads

A Story from the Heart Part II

What Tourist Industry?

Photos and Text by Tim Kendall

This article is the second in a series by Tim Kendall, a blues enthusiast and photographer from the United Kingdom, who, along with musician Bill Barth in the 1990s, purchased “The Crossroads” bar in Clarksdale, Mississippi from Mt. Zion Memorial Fund founder Raymond “Skip” Henderson. Click HERE to read Tim Kendall’s first part of the series.

Bill Barth and I had bought ‘The Crossroads’ bar in Clarksdale under the impression that there was some kind of tourist industry in the Delta. There was in fact no tourist industry to speak of in the entire Mississippi Delta, let alone Clarksdale.

That first visit to the Mississippi Delta had given me plenty of food for thought. Bill Barth and I had bought ‘The Crossroads’ bar in Clarksdale under the impression that there was a tourist industry in the Delta. There was no tourist industry to speak of in the entire Mississippi Delta, let alone Clarksdale with its boarded-up storefronts and decaying buildings.

Tourist coaches, such as they were, went from Memphis down to Natchez via Vicksburg and on to New Orleans, by-passing the Mississippi Delta altogether. In Memphis tourists would visit Elvis’s home, Graceland, followed by a quick tour of Beale Street and a visit to Sun Records; that covered the music! In Vicksburg they would visit the National Military Park and Cemetery, a museum displaying American Civil War artefacts and then on to Natchez.

[For more on plantation tourism, please see Shannon Evan’s blog post on “White Supremacy & Historic Preservation” in Mississippi]

Natchez; sitting on the banks of the Mississippi, renowned for its antebellum mansions in Neo-Classical, Greek Revival and the French Colonial styles. The plantation mansions are spectacular, their towering Doric columns, sweeping staircases and extensive balconies all built on slavery and cotton. It was only in 2021 that a section of the Natchez National Historical Park was dedicated to the memory of the second largest slave market in the United States and the victims that passed through it.

In the mid 1990s, most white southerners were not keen to mention the history of the slave trade and its importance to the Southern economy.

The tourist experience was still very "Song of The South."

A plantation experience that was ‘Gone with the Wind’ White Confederate oriented, except Memphis for a bit of Rock ‘n’ Roll and a look at Beale Street. Beale Street; once a magnet for black musicians was famous for its many bars, clubs and theatres. Thronging with partygoers at night it had been awash with black music. In its heyday W.C. Handy, the great black composer and band leader, had lived on Beale Street. Beale had been an important showcase for both Black American music and culture.

I was taken aback to find that in the 1990s Beale Street was like a film set; literally. Many of the buildings had been pulled down leaving just the fronts like a giant studio set. It was, however, the only real nod to the influence of Black American music and culture. The original Stax recording studio in Memphis, which had issued a stream of soul, blues, gospel and funk, had long been demolished.

Memphis label Satellite Records, founded in 1957, had changed its name to Stax Records in 1961 then, with Booker T. & the M.G. ‘s as house band, and artists like Sam and Dave, Otis Redding and Isaac Hayes making hit records one after another and providing backing for others, Stax became a legend. The label’s iconic logo, a distinctive black and white image of a fist thrust up in a black power salute, was a bold statement that resonated with the Civil Rights Movement of the era. There was no trace left of Stax in the 1990s, although it has since been revived and re-invented but with fingers clicking to the music rather than the iconic Black Power salute.

On ‘Beale’ there had been some attempt at revitalization. The street was clean and neat and there was BB King’s bar with live music but as Mary Beth Bauermann put it in an article on Pulitzer.org “even now in 2023; continue walking toward Fourth Street and you’ll find the historic buildings, theatres, and museums—perhaps the most direct links to Memphis’ Black history. But they are mostly empty and strikingly quiet. Across the United States, communities are having mixed success in efforts to restore historic theatres and districts, illuminating the challenges of reviving city neighborhoods that have suffered from decades of structural racism.

We were trying to start a business in the 1990s showcasing Black American music and culture; this was going to be be a long slog. When Bill Barth and a handful of friends had put on the first Memphis Country Blues Festival at the Overton Shell in Memphis in 1966, it was with the express purpose of showcasing Black Delta musicians and making them a little money. For context, it was also in an environment where, in that same venue, the week before the first festival the Ku Klux Klan had held one of their rallies.

We thought that things would have moved on more than they had!

Jim O’Neal’s ‘Rooster Blues record label was just a few doors down from the bar in Clarksdale.

Jim a blues scholar, enthusiast and researcher, had founded ‘Living Blues’ magazine in 1970 with Amy van Singel in Chicago. Housed in what had originally been an ice cream parlor the building was shaped like the Pilot House of a Mississippi River Boat. The paddle steamer’s bridge, complete with two narrow, tall, black chimneys, was covered by peeling, once white, paint. It now had the air of a decommissioned riverboat left to rot in the soft mud of the Mississippi River rather than the gay image it once displayed. The building had seen better days, like the rest of Clarksdale. Jim had a small recording studio in the back of the building and the front was a shop selling records, compact discs, memorabilia, and folk art. Jim was also the key instigator and organizer of the Sunflower River Blues Festival in Clarksdale. He recorded and promoted local Black musicians such as James ‘Super Chikan’ Johnson and the late, great Lonnie Pitchford. In fact, Jim was the tourist industry in Clarksdale.

The Delta was, and still is, very rural and very poor, the poorest part of the poorest state in the USA. Unless you were a real dyed in the wool Blues fan there was little to give you any idea of just how important this area was to the foundations of modern popular music, or the rich culture and history, that if you could just scratch the surface, still dwelt here.

The wonderous thing was though, much to my surprise, the rich culture and music of the Mississippi Delta was still very much alive.

I had no idea what to expect when I’d first arrived in the Delta. I thought that a young generation of Black Americans would be walking around with ghetto blasters stuck to their ears, street dancing, and listening to hip-hop and contemporary R&B from The Fugees, Wu Tang Clan, and Jay-Z, which was what a lot of kids listened to and identified with. But, importantly, the music that we call Blues was not only still alive, it was revered, cherished, and nurtured by the communities that had given birth to it–Black Americans from the Deep South.

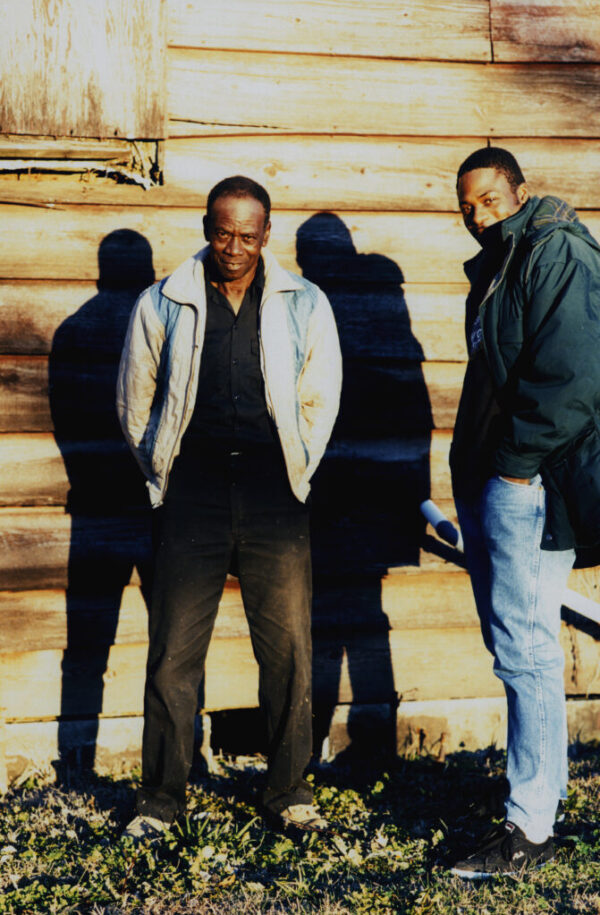

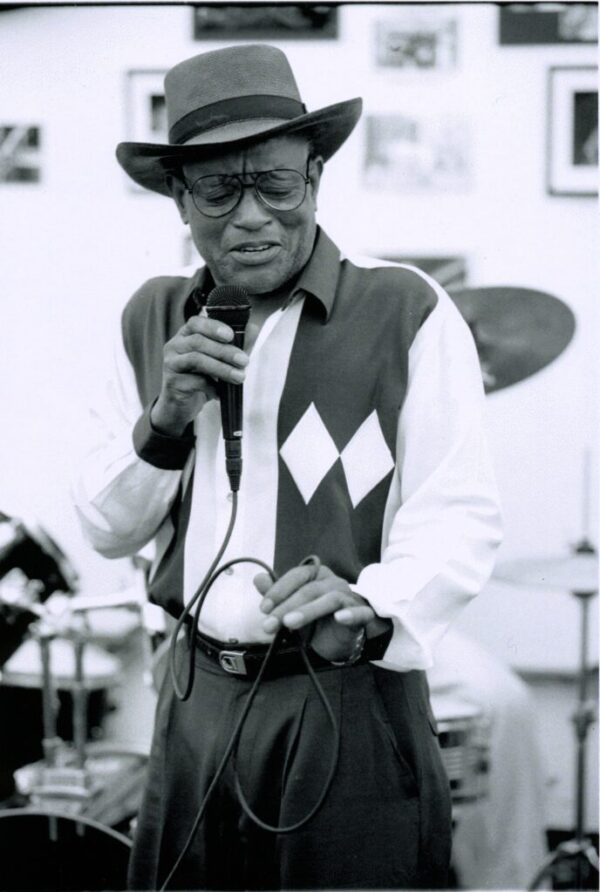

Mr. Johnny Billington was one such Black American who had a lot to do with keeping the blues alive in the Delta. Born in Quitman County in 1935, Johnny Billington had listened regularly to the popular King Biscuit Time radio show. Featuring the great Sonny Boy Williamson II (Rice Miller) on harmonica and Robert Lockwood Jr. on guitar, the show inspired the young Johnny to learn the guitar himself. Then, a young Johnny Billington moved to Chicago and played with greats, like Elmore James and Muddy Waters for more than twenty years before returning to Mississippi.

Returning in the late 1970s, “Mr. Johnny”, as he became known to his students, began teaching children auto mechanics, pride in themselves and their culture, and expertise in that culture’s primary musical form, The Blues.

“Mr. Johnny” played an important part in maintaining Delta Blues as a living cultural tradition.

I rarely met a young musician in the Delta who hadn’t felt his influence, an influence which lives on in the many local musicians who learned from him, and in the continuing Delta Blues Education Project now based out of the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale. The project was instigated with the help of then-curator John Ruskey, and later involved New Hampshire-based musician T.J. Wheeler, who helped to take the project into schools.

Walking through the doors of The Delta Blues Museum in 1997 there was little more than a large room in the local branch of the Carnegie Public Library with a young and enthusiastic John Ruskey its curator. John, a writer and artist is also an expert canoeist an enthusiast of both Blues and Mark Twain and an accomplished musician. After falling out with the Museum director in 1998 John set up ‘The Quapaw Canoe Company’, organizing expeditions of the lower Mississippi River. Ruskey, nicknamed ‘The River Rat,’ is still there, painting, writing and supporting the local community, whilst taking interested parties out on the great Mississippi. Importantly for Bill and I though, John provided one more attraction for visitors and showed that there were others with a passion for the area’s history and culture that were willing to invest in it.

As I said, there was no tourist industry to speak of in Clarksdale. There was a handful of places to visit but no overall focus, nothing bringing key elements together and nothing happening on a weekday, the building blocks were there though. This was after all Clarksdale Mississippi, home to so many great musicians at one time or another, Sam Cooke, John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, and Muddy Waters to name just a few.

But it wasn’t until I arrived in Clarksdale that I discovered that it was also home to Tennessee Williams. Clarksdale was where Tennessee’s grandfather, Walter E. Dakin had been rector of St. George’s Episcopal Church. The young Tennessee had spent long periods of his childhood here with his grandfather and many of his plays and stories were set in the area. This was great news to me and Bill as it gave another dimension to the visitor ‘offer’, and who doesn’t love Tennessee Williams?

The MDTWF, or Mississippi Delta Tennessee Williams Festival, to give it it’s full and unwieldy name, was founded with a grant from The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in 1992.

Panny Mayfield, Clarksdale journalist and photographer helped to write the bid with Dr. Vivian Presley, President of Coahoma Community College. Panny was not only the driving force behind the festival but was supportive of our project. The Tennessee Williams Festival had only been going for four years when Bill and I turned up. Also, as I mentioned earlier, there was the Sunflower River Blues Festival, the biggest event in Clarksdale’s diary and the town’s main attraction for Blues Tourism. Founded by Jim O’Neal and Dr. Patricia (Patty) Johnson, in 1988, the festival had been going for just eight years but already drew blues fans from all over the world. The Festival was so real back then, it was like someone in town had decided to throw a party and invite everyone in the world. Importantly though, it was growing in numbers every year.

Hopson Farm and Commissary, owned by James Butler, was another business striving to survive and develop with a tourist industry. Three miles outside of Clarksdale on Highway 49, Hopson’s was notable for a couple of things. For one, the great blues piano player Pine Top Perkins had once worked there as a tractor driver. Also, in 1944, Hopson’s had been the first to trial and introduce The International Harvester Mechanical Cotton Picker, or IHMCP (I just made that acronym up).

Everything in the Delta seemed to be a mouthful and take a long time. They even have a name for the phenomenon, “Delta Time”, similar to “Manana Manana.”

Cotton planters had been seriously looking into mechanizing since the 1930s when large numbers of African Americans left the Deep South to work in Chicago, St Louis and anywhere else north of the Mason Dixon line. Anywhere they could get away from the highly discriminatory and restrictive Jim Crow Laws in what has become known as “the Great Migration.”

The Hopson Commissary was a great barn-like space where James had installed a bar. He was leasing the space for weddings and dinners and had live music every Saturday night. I once attended an Easter Banquet there at the invitation of Bill Luckett. James Butler was I thought one of a few white people with the vision to see the potential that the area had based on Black American Culture. After dinner, I just about remember spending the whole night in the back room of Hopson’s with James drinking Tennessee whiskey and discussing our vision for Clarksdale. I have to admit the details of the conversation are a bit hazy but I did form the opinion that James was a remarkably likeable bloke with a positive attitude, considerable resilience and a large stock of good whiskey that he was happy to share.

So here we were with a business selling beer, food and live music in a town which had few regular visitors, and little money, where most of the streets were lined with boarded-up shops and I had just found out the legal age limit on alcohol was 21! Who the hell were our customers going to be? There were though a handful of people who knew what Clarksdale meant to the development of modern popular music, the value of its cultural history and who believed that others should know about it too. Charlie Kendall (no relation to me) was one of those people. A returned son of Clarksdale Charlie had been a successful radio DJ in New York and on The West Coast. Charlie had returned home to Clarksdale and bought the local radio station, WROX.

WROX began transmitting on June 5 1944 from Delta Avenue in Clarksdale. In 1947, Early Wright was hired as the first black radio announcer in Mississippi. He hosted local musicians like Sam Cooke, B.B. King, Little Milton, Pinetop Perkins, Elvis Presley, and Muddy Waters. Ike Turner also became a DJ at WROX with his own show. Ike played live on the show sometimes with his band the Kings of Rhythm. The band included his childhood friends Raymond Hill and Jackie Brenston, the latter credited with writing the first ‘Rock & Roll’ single ‘Rocket 88’.

The city of Clarksdale was–and is–important to American history and culture, particularly Black Culture and more significantly Black Music. We needed to work out how to let people know this and a way for them to experience the unique and vibrant music and atmosphere of the Mississippi Delta in as real a way as possible, without getting mugged, lost, shot or ripped off. This was not going to be easy (or cheap). It was a bit overwhelming, in fact, and felt like I was in a lost episode of Mission Impossible.

“Your mission, Tim, should you decide to accept it, is to create a tourist industry in the Mississippi Delta. As always, should you be caught, killed or bankrupted the Secretary will disavow any knowledge of your actions. This tape will self-destruct in five seconds.”

Now to work!

Time for a ‘To Do List.’ The front of the bar looked just like the many derelict buildings in Clarksdale and was my first priority. If we were going to attract an international clientele of tourists, the front of the building needed smartening up; it needed some work and some paint. I got on the phone to Terry (Big T) Williams,

“Hey Terry, want to earn some money?”

“Sure Teaum, whacha want?”

I had to get used to my name being Teaum!

I picked Terry up from wherever he was staying, and we went to the Crossroads Bar to decide what we needed. Apart from brushes and paint, it looked like we could use a power drill and a few basic tools. There were bits falling down the front from the top of the building and a striped retractable awning that needed some work.

Terry suggested that we visit a pawn shop on 4th Street, the main highway, where we could get what we needed cheaper than the hardware store. This seemed like a good plan, and we hopped in my hire car and shot up to the pawn shop.

If you’re American, you may not understand a Europeans reaction to seeing hand guns, let alone automatic weapons, casually displayed. Underneath a glass topped counter in the pawn shop, alongside some electric drills and a variety of other small power tools, were three or four hand guns, and they were cheap! One in particularly stood out to me–a bright shiny revolver, which looked to be a fairly large caliber, although I’m no expert.

I was born on a farm, I grew up with shotguns hunting game and vermin. I’ve also been around a bit. I’ve been held up at gunpoint and had men brandishing a variety of weapons at me in remote places. I’ve watched someone smoke opium through a used US rocket launcher and one time, in an Irish bar in Amsterdam, a young woman on the bar stool next to me dropped her handbag, hitting the floor with a distinctive heavy thud, a snub-nosed revolver popped out. “Sorry,” she said, making brief eye contact to check my reaction as she stuffed it back in.

But to see weapons, that in Europe we associate purely with violence, casually on display with other objects in a pawn shop seemed very strange, it actually made me shiver. I seem to remember that it was only about $20, I turned to Terry and said “what do you need to buy one of those” “a driver’s licence” Terry replied. Jesus, the local paper was bemoaning the number of armed robberies in the area and here, I thought, right in front of me was the cause, poverty and cheap guns, what a heady mix. Anyway, we just bought some power tools, went to another store for some blue paint and brushes then back to The Crossroads.

Terry got to sorting out the front of the bar whilst I turned my attention to our biggest problem. How were we going to run a bar in Mississippi from Amsterdam? We had inherited a someone with the bar, which was unexpected. I don’t know if Skip had told Bill and Bill had forgotten to tell me or if it had slipped Skips mind altogether, either way no one had told me about ‘Miss’ Sarah Moore. Sarah was a fantastic cook and had run the whole place on her own for some time. You know someone is a great cook when they make something as simple as breaded catfish with homemade coleslaw and hand cut chips (fries) and you can’t get enough of it, I still dream about Miss Sarah’s catfish, she cooked it to mouth-watering, melting perfection.

Just over the road from the bar was the county jail. Most days, Miss Sarah would send her kids over with trays of food covered in gingham cloth. It was like something out of a Tennessee Williams play. But our association with Sarah was short-lived. Sarah didn’t trust Bill or me and I’m not surprised, what we were doing seemed mad. I don’t think Sarah could understand why a skinny Englishman and a six-foot-four New York Jew were interested in Clarksdale, and she didn’t think much of our lawyer or our accountant. Sarah Moore passed away in 2009 but is remembered in the Juke Joint Festival’s ‘Miss Sarah Awards’. Named in her honor and presented every year at the opening of the festival in April. The Miss Sarah Awards for contributions to blues music, tourism and the City of Clarksdale.

The Juke Joint Festival began in a loosely organized way the year we took over The Crossroads. I think it was called the April Blues Festival or Clarksdale in April or Spring in Clarksdale, or something like that anyway, I can’t quite remember. It was partly sponsored by the local Department of Trade and Commerce. We were all just trying to think of reasons to stay open and get people to come to Clarksdale. I read in a British newspaper, The Guardian, recently that the 2023 Juke Joint Festival attracted some 10,000 visitors, that’s as many as the larger Sunflower River Blues Festival achieved in 1997. I think the first spring festivals were just a few hundred, but it was a start. Crucial to any tourist industry is providing customers with what they want and expect, if people come for music then music they must have. The early incarnation of the Juke Joint Festival was a recognition that there had to be more than just the Sunflower River Blues Festival in August. Blues Music was what people came to Clarksdale for and everyone needed to pull together to provide as much of it as possible so that tourists had a reason to come for more than ten days in a year.

On John Ruskey’s recommendation, I interviewed a local nurse by the name of Evelyn (Mini Gal) Turner as a prospective manager for the bar. Evelyn had run bars and Juke Joints before and could use technology like email to keep us informed about what was happening. Evelyn was well tuned in to the local music scene through her friendship with James ‘Super Chikan’ Johnson. Importantly, Evelyn also got on with our lawyer, William O. Luckett Jr, or Bill to everyone who met him. Bill Luckett was one of the genuinely nicest people I have ever met. I was so sad to read of his passing, I can’t imagine Clarksdale without him. Anyway, for a while Evelyn and Sarah tried working together but that didn’t go well for either of them. So, Sarah soon left and a year or so later opened her own place just up the road from The Crossroads. Sarah continued to do business for longer than we survived.

Evelyn was just who we needed to be able to continue the business. The first thing Evelyn suggested, as there was no cash register in the bar, was that we get a modern electronic till to keep track of the money so there could be no misunderstandings, I was impressed. We drove up Highway 1 and over the Mississippi into Helena Arkansas. Helena was home to the King Biscuit Time radio show and was now also home to the annual King Biscuit Blues Festival. First broadcast on November 21 1941, featuring Sonny Boy Williamson II and Robert Jr Lockwood, the show was an important part of Blues history.

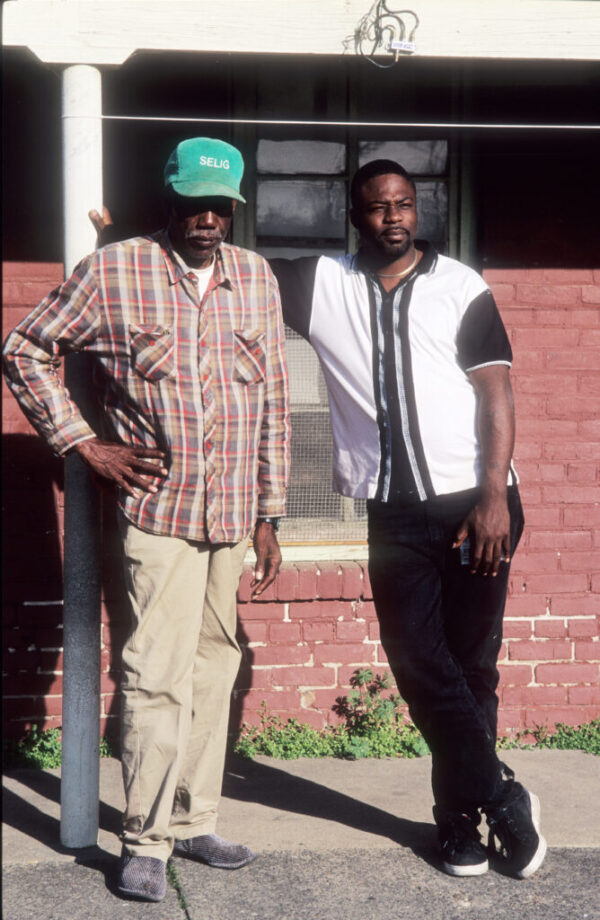

I found it hard to fathom that the area wasn’t crawling with tourists, I was constantly, ridiculously excited and awed the whole time I was there. Bill Barth had been a key figure in the Blues Revival in the 1960s more than thirty years before. Where was everybody? A clue to the dearth of tourists might be found in my first visit to Helena with Terry Williams a few months previously. Terry had for a while replaced Big Jack Johnson in the band, The Jelly Roll Kings. The Original line-up included highly renowned Delta blues musicians–Frank Frost on harmonica and vocals, Sam Carr on drums, and Big Jack on guitar. Terry had taken me to meet Sam in Tunica, where he worked as a tractor driver, and then suggested we go over to Helena to see Frank.

Terry and Frank had sat on the side of the road by the car chatting whilst I got a camera out of the boot (trunk) and started taking pictures. After about half an hour, Terry said we’d better be going. I hadn’t been paying much attention to anything except Frank and Terry. So when Terry flicked his head to indicate I should look around, I realized that we were surrounded by guys slowly closing in on us.

“C’mon Teaum, let’s get outta here ‘fore we get trouble.”

So we did. Helena had a notorious crack cocaine problem at the time as did many Delta towns and indeed, towns right across North America. I realized that if we hadn’t been talking to Frank I’d probably have lost the car, my camera’s and maybe a whole lot more already.

This was not going to be an easy place to sell to tour companies.

Anyway, back at the shop that sold cash registers in Helena, Evelyn and I bought an up-to-date electronic register that was programable and recorded all transactions. Luckily, Evelyn understood the salesman’s instructions on how it worked because I did not. In fact, I never got to grips with anything but the basics of that machine.

Evelyn and I got the cash register back to the bar, and she set it up. In a few days, Terry had painted and cleaned up the outside of the building, and we acquired a new sign made of Cypress wood from a Delta bayou–tough as anything–and in the shape of our new logo, Blues Crossroads, with the word Blues on a guitar over the Highway 61 and 49 signs on either side of the word Crossroads.

Finally, the building looked great. We had a manager, a new logo, the name Blues Crossroads over the door, and the business and logo registered through our lawyer. We were ready for business.

We were trying to achieve was a place where tour companies felt safe and confident to bring their customers but was still real enough to experience the Delta Blues and Delta culture as it was. It felt like we were getting there. Now I had to get back to my family in Amsterdam, my children were missing me and, I hoped, my wife. But I would be back by the beginning of August for the next Sunflower River Blues Festival.

TO BE CONTINUED…

![Montroy Cemetery Montroy Cemetery near Moon Lake in rural Coahoma County, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Montroy-Cemetery-1_Edit-1024x656.jpg?resize=500%2C320&ssl=1)

![His Place His Place Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/His-Place-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C763&ssl=1)

![Three crosses at the Crossroads Three crosses at the Crossroads in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Three-crosses-at-the-Crossroads_Edit-1024x672.jpg?resize=800%2C525&ssl=1)

![Country Church Near Coahama County Country Church near Coahama County, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Country-Church-Nr-Cohama_Edit-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1712&ssl=1)

![Rooster Blues Jim O’Neal’s ‘Rooster Blues’ label [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Rooster-Blues-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C760&ssl=1)

![Farrell Post Office The post office in Farrell, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Farrell-Post-Office_Edit-1024x666.jpg?resize=800%2C520&ssl=1)

![Mr Johnnie Billington at The Crossroads Mr. Johnnie Billington performing at The Crossroads Bar [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Mr-Johnnie-Billington-at-The-Crossroads_Edit-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C762&ssl=1)

![Johnny Billington smiling Mr. Johnnie Billington smiling during his performance at The Crossroads Bar [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Johnny-Billington-smiling-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1804&ssl=1)

![Hopson Commissary before it transformed into the Shackup Inn Hopson Commissary [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Hopson-before-it-was-The-Shackup-Inn-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C776&ssl=1)

![Hopson's Commissary with an older model cotton picker Hopson's Commissary with an older model cotton picker [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Hopsons-with-Cotton-Picker_Edit-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C769&ssl=1)

![Hopson entrance before it was The Shackup Inn Hopson entrance before it was The Shackup Inn [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Hopson-entrance-before-it-was-The-Shackup-Inn-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C776&ssl=1)

![This Levee Is Not A Public Road This Levee Is Not A Public Road [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/This-Levee-Is-Not-A-Public-Road-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1806&ssl=1)

![Females dancing at the Crossroads Bar Women dancing and having fun at "The Crossroads" Blues Bar [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Female-Audience-Crossroads-1024x687.jpg?resize=800%2C536&ssl=1)

![The Bar as we found it_Edit The Crossroads Bar upon Tim Kendall's arrival in Clarksdale, MS in 1996 [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-Bar-as-we-found-it_Edit-1024x681.jpg?resize=600%2C399&ssl=1)

![Row of shacks with moon Row of shotgun shacks outside Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Row-of-shacks-with-moon-1024x655.jpg?resize=500%2C319&ssl=1)

![Delta Blues Education Program Delta Blues Education Program in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/DBEP-Closed_edity-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1245&ssl=1)

![Stoval Farms Entrance The entrance to Stovall Farms [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Stoval-Farms-Entrance-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C779&ssl=1)

![Getting the Museum Float ready John Ruskey (in the hat) getting the Delta Blues Museum Float ready for the Christmas Parade [Photo: Panny Flautt Mayfield © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Getting-the-Museum-Float-ready-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C762&ssl=1)

![Evelyn 'Mini Gal' Turner Evelyn 'Mini Gal' Turner [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Evelyn-Mini-Gal-Turner-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C759&ssl=1)

![Crossroads Bar The Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS after renovations [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1996]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Crossroads-bar-After-1024x706.jpg?resize=500%2C344&ssl=1)

December 23, 2023 @ 5:55 pm

Another good read, Tim ! Packed with really interesting information and insights.