I Went Down to The Crossroads

A Story from the Heart Part III

The 97 Festival

Photos and Text by Tim Kendall

This article is the third in a series by Tim Kendall, a blues enthusiast and photographer from the United Kingdom, who, along with musician Bill Barth in the 1990s, purchased “The Crossroads” bar in Clarksdale, Mississippi from Mt. Zion Memorial Fund founder Raymond “Skip” Henderson.

Click HERE to read the FIRST part of the series.

Click HERE to read the SECOND part of the series

Holy shit it was hot! As soon as I stepped out of Mara’s house my clothes were soaked with sweat. Whenever you came out of an air-conditioned building or car into the sweltering heat, the sweat instantly sprang from your every pore, sticking clothes to your body like a wet T-shirt competition.

Then, as soon as you stepped into the next air-conditioned environment, you were freezing. I got into my hire car and froze for the few minutes’ drive across the Second Street Bridge over the Sunflower River and pulled up outside the Blues Crossroads, the bar that Bill Barth and I had bought the previous year. The concrete Second Street bridge was constructed in 1936 as part of The New Deal Public Works Administration Project, along with The Clarksdale Auditorium in that uniquely American Modernist Style; I liked it.

In the few seconds that it took me to get from the air-conditioned car into the bar I was soaked again. It was August, with 98% humidity and temperatures in the high 30s Centigrade. Now I understood why so many people in Mississippi had colds all summer long.

Blinded by the sudden darkness I stopped inside the door as my eyes adjusted to the bar. It was just after mid-day, any shadows outside were hiding underneath everything trying to get out of the blinding white sunlight. As my vision returned, my hearing also focused. Down at the other end of the narrow bar room, sitting up by the bar nursing a cold beer, I could see Jim O’Neil talking quietly with Evelyn “Mini-Gal” Turner, the manager, his voice a low hum.

“Shit Evelyn,” he complained, “I don’t know if he’s going to play at all. He was really pissed off with me, shoutin’ down the phone!”

Jim O’Neil was the proprietor of Rooster Blues, a store and record label a few doors down from the Crossroads Bar. Along with Dr. Patricia Johnson, he had also founded The Sunflower River Blues Festival in 1987. In fact, Jim had pulled off a bit of a coup for the festival in 1997. Free to attend, it was a showcase of the incredible local musicians and Gospel singers that proved the living, beating, heart of the Mississippi Delta. In 1997, the festival had hardly any money to pay the musicians. Yet, somehow Jim had convinced Clarksdale native Ike Turner to fly from California and headline the event at his own expense.

Ike Turner’s reputation had been all but destroyed by the revelations of domestic abuse in the film, What’s Love Got to Do With It.

But still, there was no denying his great talent and skill as a musician and band leader, nor his influence on the development of modern popular music. As a young man, Turner had spent a lot of time in the local Clarksdale radio station, WROX, and he worked as a talent scout for Memphis music producer Sam Philips, of Sun Records, tracking down such blues artists as Howlin’ Wolf as well as Johnny “Guitar” Watson for the Bihari Brothers and Meteor Records. Turner had also recorded with his own band, The Kings of Rhythm, in Memphis, just 60 miles north of Clarksdale.

Rock n’ Roll, the term, is really just a label adopted for Rhythm and Blues (R&B), making it more acceptable to a white audience. R&B was Black music, and what we now call Rock n’ Roll was a development of R&B that had become popular with Black audiences between Memphis and New Orleans during the 1940s. It was like an up-tempo Jump Blues with electric guitar. The term Rock n’ Roll is often attributed to a white disc jockey named Alan Freed. In 1951, Freed, a lover of R&B, had taken inspiration from a single called “Sixty Minute Man,” by Billy Ward and his Dominoes. “I rock ‘em, roll ‘em all night long,” was the line, apparently.

Later that same year, Ike Turner and bandmate Jackie Brenston had recorded “Rocket 88” with Sam Phillips in Memphis, as Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats. “Rocket 88” is now widely regarded as the first Rock n’ Roll single. The heavily distorted electric guitar and saxophone, the distortion partly the result of a damaged speaker, combined with a heavy backbeat and Ike’s stride piano is as exciting now as it was in 1951. The addition of the distorted electric guitar and Ike’s up-tempo piano gives “Rocket 88” the feel of Louis Jordan Jump Blues on rocket fuel!

Anyway, back at the Crossroads Bar in 1997, Jim O’Neil was moaning to Evelyn “Mini Gal” Turner—while sipping a cold beer—about his problems with Ike. At first, Ike planned to perform solo, but once he arrived in Clarksdale he decided to fly out the whole Ike Turner Review at his own expense. This was around nine or ten musicians, singers, and dancers with a complicated show that needed to be rehearsed, and Jim had no space for them to rehearse. This was a problem, and Ike was pissed off.

Evelyn handed me a beer and turned to Jim, smiling while she picked up the phone. “Don’t you worry about that, Jim,” she chortled, “What hotel’s he at?”

Jim recited the phone number of Ike’s hotel room, and we both watched curiously as Evelyn dialed the number. “Hey there, put me through to Ike Turner, please? Tell him it’s his first cousin, Evelyn.”

Jim and I looked at each other, eyes widening. Evelyn “Mini Gal” Turner! It had never occurred to us! After a lot of incomprehensible screaming and laughing, Evelyn told Ike that she managed a bar and was sitting there with a PA, guitar amps, a stage, full drum kit, and floor space. I was astonished! Jim was visibly relieved, and Evelyn was grinning from ear to ear.

“Stick around, Jim,” she laughed, “He’s in a better mood now.” But Jim thought it better to—temporarily at least—retire to his store and give Ike some time to settle into his new digs.

About twenty minutes later, two big black stretch limousines pulled up outside the bar, and people started pouring out, carrying instrument cases, laughing, and shouting to each other.

Ike Turner had been out of jail for a couple of years after an 18 month stretch for cocaine possession.

Although older, he was looking stronger and fitter than in any of the pictures I’d ever seen of him and Tina from the 1960s and 70s. His current wife, Jeanette Bazzell Turner, was an ash blonde. Talented and intelligent, Jeanette managed the business side of things as well as being lead vocals. Evelyn briefly introduced me to Ike, and he introduced Jeanette, who chatted away to me while the band set up and everyone got used to the place.

It was obvious that this, Ike’s first visit to his home town in many years, decades even, was a very emotional event for him and he really appreciated Evelyn reaching out and offering him a place to rehearse. Having seen the 1993 film What’s Love Got to Do with It and read I Tina, the co-written autobiography of Tina Turner that the film was based on, the introduction had always struck me. It talks about Ike Turner’s childhood in Clarksdale; his early struggles not just as a musician, but also with the abuse he suffered as a child. I had always felt that the introduction to I Tina gave some context to what it was like growing up as a talented and ambitious young Black man in the Jim Crow South. It’s still no excuse for his domestic violence, and I think it was generous of Tina to frame the larger story of their relationship within the gender constructions of Black masculinity in the South.

“[Ike Turner] threw hot coffee in my face, giving me third-degree burns. He used my nose as a punching bag so many times that I could taste blood running down my throat when I sang. He broke my jaw. And I couldn’t remember what it was like not to have a black eye.”

One night, Tina recalled how her ex-husband picked up a wooden shoe stretcher and attacked her. “Ike knew what he was doing,” she wrote, “if you play guitar, you never use your fists in a fight. He used the shoe stretcher to strike me in the head, always the head.”

“I was so shocked I started to cry,” Tina continued, “Ike ordered me to get on the bed. I hated him at that moment. The very last thing I wanted to do was make love, if you could call it that. When he finished, I laid there with a swollen head, thinking, ‘You’re pregnant and you have no place to go. You really have gotten yourself into something now.’”

I teach adults with barriers to learning. This includes a high proportion of individuals with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma related issues. I can relate to a quote from a 2021 interview by Julie Miller in Vanity Fair with filmmaker T.J. Martin, who co-produced the HBO documentary Tina.

“Regardless of the era we’re in, it took her [Tina Turner], and continues to take, a lot of courage for her to kind of wake up and make the decisions to continue to survive. This idea that her trauma is something that she’s actively continuing to process and she has to make a decision about every day for the betterment of her mental and emotional well-being…is something I find really admirable.”

My teaching experience tells me that trauma never leaves you. You just learn to cope with it, if you’re lucky. Ike Turner’s physically abusive and controlling behavior towards Tina was abhorrent, and it clearly reflected his experiences with physical abuse as a youth. Instead of dealing with his own trauma, however, he took it out on Tina.

In 1997, I did not talk much to Ike, because he seemed to me to have a macho vibe about him that I’m never comfortable with. In fact, I’m not comfortable around all men who feel the need to display their hypermasculinity. I got on well with Jeannette, his wife, though.

While thinking about all this, I came across a great quote by Toni Morrison in a New York Times article from 1971. The article is titled “What the Black Woman Thinks About Women’s Lib.” I think it speaks to Ike and Tina’s relationship as well as being an homage to the incredible fortitude and heroism of Black women in America.

“For years in this country there was no one for black men to vent their rage on except black women. And for years black women accepted that rage—even regarded that acceptance as their unpleasant duty. But in doing so, they frequently kicked back, and they seem never to have become the “true slave” that white women see in their own history. True, the black woman did the housework, the drudgery; true, she reared the children, often alone, but she did all of that while occupying a place on the job market, a place her mate could not get or which his pride would not let him accept. And she had nothing to fall back on: not maleness, not whiteness, not ladyhood, not anything.”

Ike Turner was not unique as a Black American, as a man, or as a musician, in his abusive relationships with women. There is a growing body of academic literature on the generational trauma of slavery leading to Black men feeling emasculated and frustrated. Most of the research was written by men though; straight, middle class, and white at that. If you are interested, I would recommend reading the rest of the Toni Morrison piece.

It’s important to listen to the voices of Black women on the subject.

Ike Turner certainly had problems in his personal relationships, but he was also a very talented and influential musician. I think it’s worth mentioning here that all of the other Black musicians I got to know in Clarksdale were absolutely lovely people, and—as far as I know—they did not have a penchant for physical violence, let alone a criminal record of domestic abuse.

Ike Turner played a pivotal role in shaping the music industry during the 1950s Rock n’ Roll era. Despite his musical brilliance, however, his legacy is forever intertwined with domestic violence and the consequences he faced for his actions. Ike had left Clarksdale around 1954 and as far as I know never returned until Jim O’Neil invited him to play the Sunflower River Blues Festival more than forty years later.

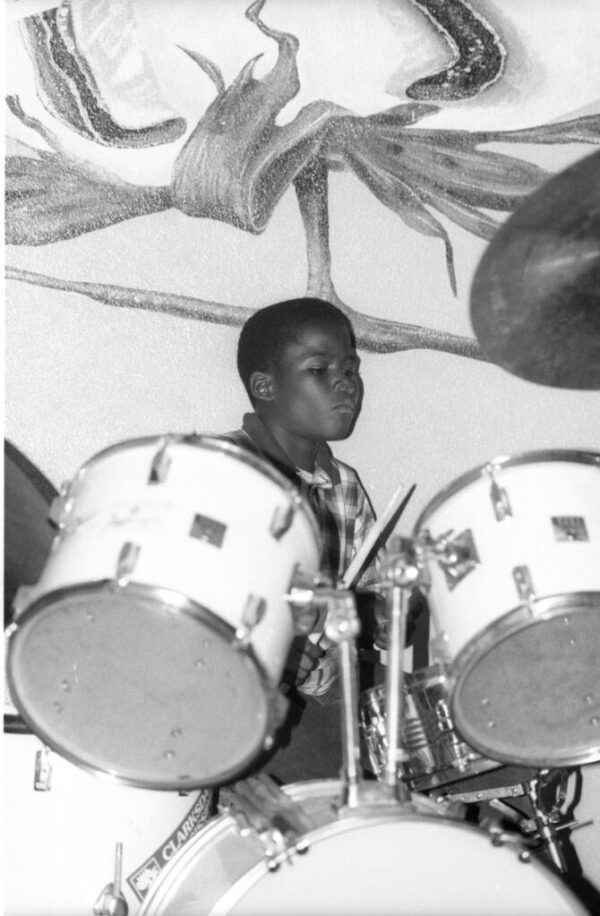

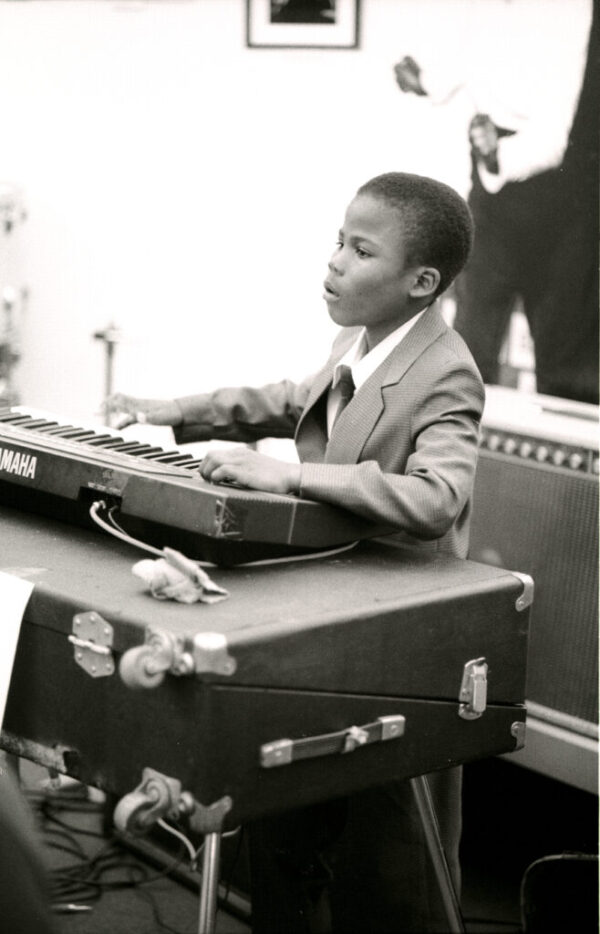

The next ten days of the festival were hectic and incredible. Little Milton, also on the bill for the festival, dropped by the bar occasionally to chat with Ike. Milton’s brass section spent a whole lot of time in the bar rehearsing a couple of numbers with Ike and the son of the late Wayne Walton, “The Singing Barber,” who played keyboards for the band while they were in town for the show. There was an astonishing amount of talent wherever you looked around the bar. Little Milton’s brass section was sitting around a table on the floor. Ike’s band members were up on the stage, and Ike was standing in between with his Fender Stratocaster, leading the whole thing. The dancers and singers were prancing in a line across the floor, singing and grooving over and over again. Customers came and went with their jaws dropping. The atmosphere was incredible!

I was personally in a complete daze throughout this time.

I said in the first of these articles that when I first came to Clarksdale I had no idea what to expect; well, it certainly was not this.

I had met some truly incredible people. Watching Terry Williams play his heart out through his guitar, driving around with the lovely Jeno Tucker, laughing and listening to his Delta stories in his old pickup, sitting quietly at the bar after hours, listening to James “Super Chikan” Johnson, Josh White, Wesley “June Bug” Jefferson, Dr. Mike and others, recount some of the tragic events that had shaped their childhoods in the racially segregated atmosphere in the Delta, and working with the fantastically good humored Evelyn “Mini Gal” Turner.

This was what I had dreamed of but had never imagined would experience.

This was THE BLUES. And not just the music, but all of it! To me, this is why THE BLUES is unequivocally Black music. Sure, white people can play the music and play it well, but that will always just be music. The real Blues, the Deep Blues, as music writer Robert Palmer put it, are a part of the lived experiences of African Americans. THE BLUES belongs to them. It is their culture.

Terry Williams is a great example. Terry may not have become internationally famous, but I have never known a better blues guitar player. With Terry, it is not about technique; it’s his identity. THE BLUES runs through his blood, and you can only really experience this live. It does not happen every time he plays–although he is always a damn good musician–but sometimes, he needs to play. If you are ever lucky enough to be around Terry Williams when that happens, believe me, you will never forget it.

The hairs on the back of your neck will prickle and stand up. Your heart will not know whether to stop or explode. And, he will leave you in awe of how a human being can speak through an instrument. I felt truly humbled, and I was very lucky to have experienced it.

The 10th anniversary of the Sunflower River Blues Festival was a turning point for tourism and the city of Clarksdale. The Notodden Blues Festival in Norway had started a year after the Sunflower River festival and, ironically, it had bigger acts already. In the 50s and early 60s, the popularity of blues in Europe was perhaps even greater than in the US. Sweden boasts the oldest blues periodical in the world–Jefferson Blues Magazine, which remains in publication today. Finland, France also have blues music periodicals that remain in publication.

There were quite a few visitors from Notodden and even Japan that year. Witnessing the return performance of Ike Turner in the heart of the Mississippi Delta was something that attracted blues enthusiasts from across the globe. In my opinion, the 1997 Sunflower festival put the city of Clarksdale and its blues history squarely in the sights of the media. Although still slow, after the 97 festival, there was a gradually increasing number of promotional articles published about blues road trips, food travelogues, and increasingly through the 2000s Clarksdale itself as the home of the blues. Getting Ike Turner back to Clarksdale energized blues tourism! From that point, whenever the blues was mentioned, Clarksdale was also noted as the home of the blues.

Jim O’Neal deserves a lot of the credit. Nice one, Jim!

![Anthony Sherrard Anthony "Big A" Sherrod in the Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/A.-Sherrard-2-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C761&ssl=1)

![Bill Barth, Cedric Burnside, and Kenny Brown Bill Barth, Cedric Burnside, and Kenny Brown talking about the blues in DenHague @ Te Norht Sea Jazz Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Barth-Cedric-Bunside-Kenn-Brown-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C752&ssl=1)

![Bill Barth & Kenny Brown Bill Barth and Kenny Brown talking about the blues in DenHague @ Te Norht Sea Jazz Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/B-Barth-Kenny-talking-Hotel-1024x662.jpg?resize=800%2C517&ssl=1)

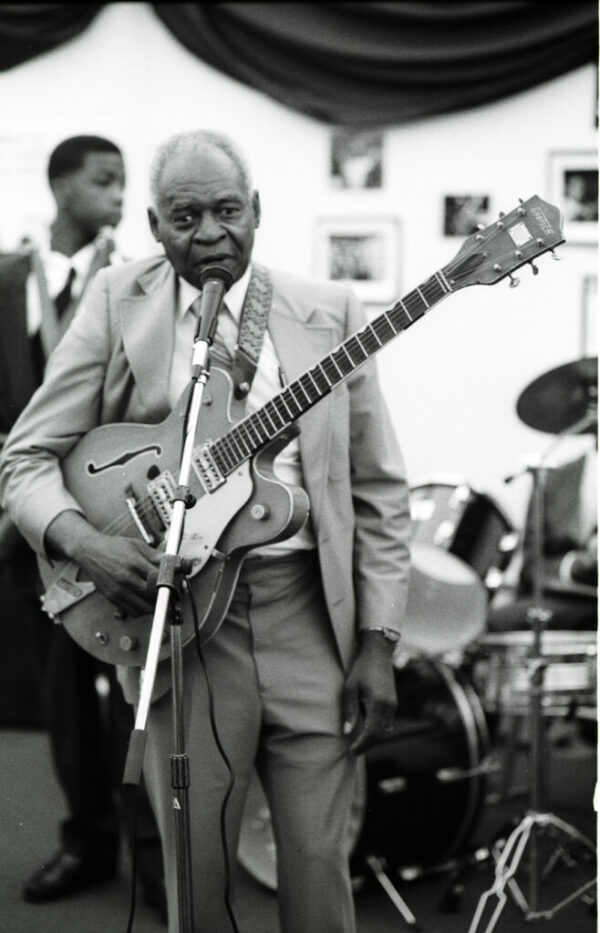

![Ike Turner Ike Turner playing guitar at the 1997 Sunflower River Blues Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ike-BW-1-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1791&ssl=1)

![Josh White & Anthony Sherrard Josh White & Anthony "Big A" Sherrod in the Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Josh-White-Big-A--scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C750&ssl=1)

![Ike Turner Rehearsal Ike Turner rehearsing in the Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ike-review-rehearsals-1-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C738&ssl=1)

![Ike-ettes and Jeanette Ike-ettes singing in the Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ikettes-Jeanette--scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C758&ssl=1)

![Ike-ettes Ike-ettes singing in the Crossroads Bar in Clarksdale, MS [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ikettes-Jeanette-Turner-centre-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C751&ssl=1)

![Ike Turner and the Ike-ettes Ike Turner and the Ike-ettes practicing before the 1997 Sunflower River Blues Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ikettes-Jeanette-Turner-right-Ike-Centre-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C755&ssl=1)

![Ike Turner playing guitar Ike Turner playing guitar prior to the 1997 Sunflower River Blues Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Ike-BW-2-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1791&ssl=1)

![R. L. Burnside about to leave for the 97 festival R. L. Burnside about to leave for the 1997 Sunflower River Blues Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/R-L-About-to-leave-for-the-gig-NSJF-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1808&ssl=1)

![Cedric Burnside Dressing Room Cedric Burnside in the dressing room prior to his performance in DenHague @ Te Norht Sea Jazz Festival [Photo: Tim Kendall © 1997]](https://i0.wp.com/mtzionmemorialfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Cedric-Burnside-Dressing-Room-NSJF_crop-scaled.jpg?resize=1165%2C1108&ssl=1)

March 11, 2024 @ 1:25 pm

I didn’t know the pictures with Barth existed, glad to see them. I think I have one with him when I was just a kid on Joe Callicutts front porch

March 12, 2024 @ 7:01 am

That’s amazing Kenny. I remember you talking to Bill about listening to him when you were a kid. I’ll message you about a link to the photos in the next few days.